Publisert: 19.05.2009 | Forfattar: Nils Georg Brekke

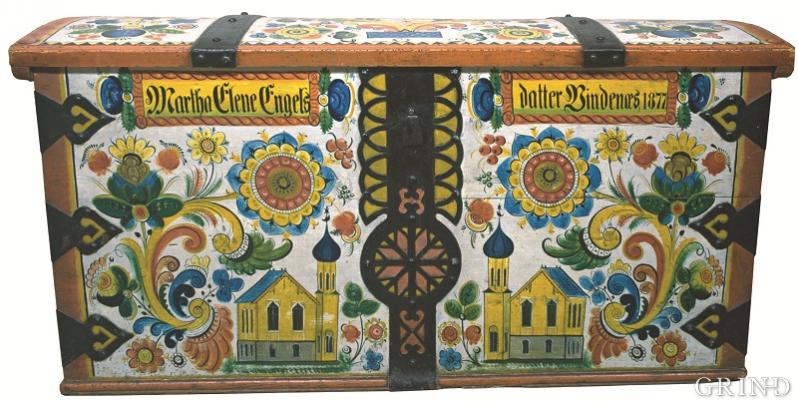

Kiste måla i 1834 av Bjørn Bjaalid, ein av dei mest elegante telemarksmålarane, (Nils Georg Brekke)

“Stay in the Peace of the Lord

from the evil Eye of Envy

as the Envied Earth

will not let itself be ploughed.

Here I eat my bread

here I fear my God

Bless each and every one

who goes in and out”

This blessing for the house is inscribed over a living room door at Rogdo in Ullensvang. The painter is Thomas Luraas from Tinn in Telemark County, and he was here in the 1850s, on one of his many painting trips to Hardanger. The inscription is well known and is to be found in several variants - an example of the cultural contacts between rural districts. Between Telemark and Hardanger influences have certainly gone in both directions. Many a west Norwegian dance tune has come back from Telemark in a new form, embellished with curls and decorations just like a blooming Telemark rose. In the west of Norway the elegant masters of the Rococo from Telemark encountered a local style influenced by the traditional motifs from Baroque and Renaissance times, presented by the early painters in Upper Hallingdal around the middle of the 18th century and by the model of the city painters of the 17th century.

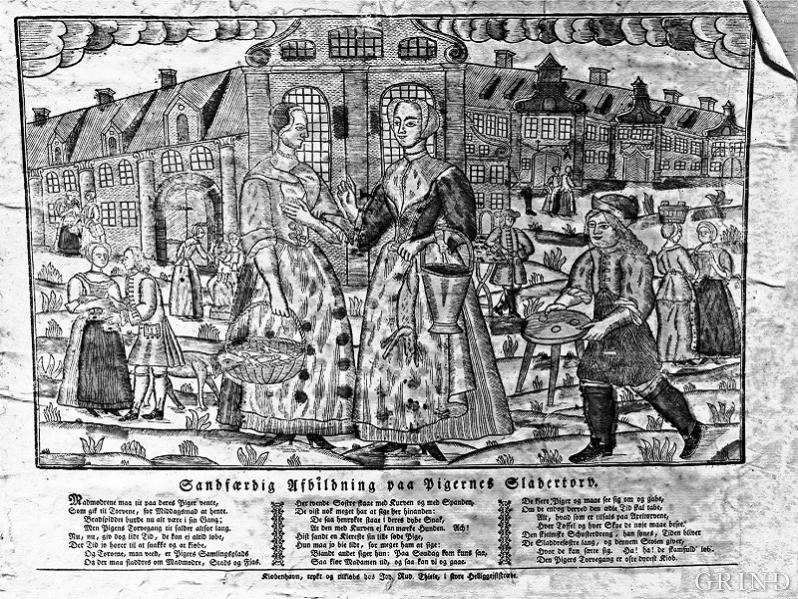

The much travelled rose painters were handicraft specialists who crossed many cultural boundaries on their wanderings. They had with them their painting books and their chapbooks (penny dreadfuls) in their bags, and in this way they were intermediaries of motifs and ideas for local society. The popular artist was both a craftsman and a cultural emissary. When the rose painter came to the farm, it was not the popular artist who came, but the painter.

Folk from the east travelling for work

The folk from Telemark were not the only, nor were they the first folk - from the east of Norway to come over the mountains to the fjord districts in order to earn money. The herring fisheries and the freight trade were such that the monetary economy made its appearance earlier here than in the mountains in the east of Norway, and the rural districts of western Norway were a good market. From the mountain districts furthest up in Hallingdal and Telemark people came after the harvest, or early in the spring on the hard crusted snow, to get a profit. A whole army of day labourers, crofters and small farmers were out travelling, haymakers, stone masons, labourers, pedlars, musicians and rose painters – and folk who went down to the coast to work in the herring fisheries. The rose painters were not first and foremost an expression of cultural expansion from the districts in Hallingdal and Telemark, they were part of labour migrations, a great commuting movement between districts.

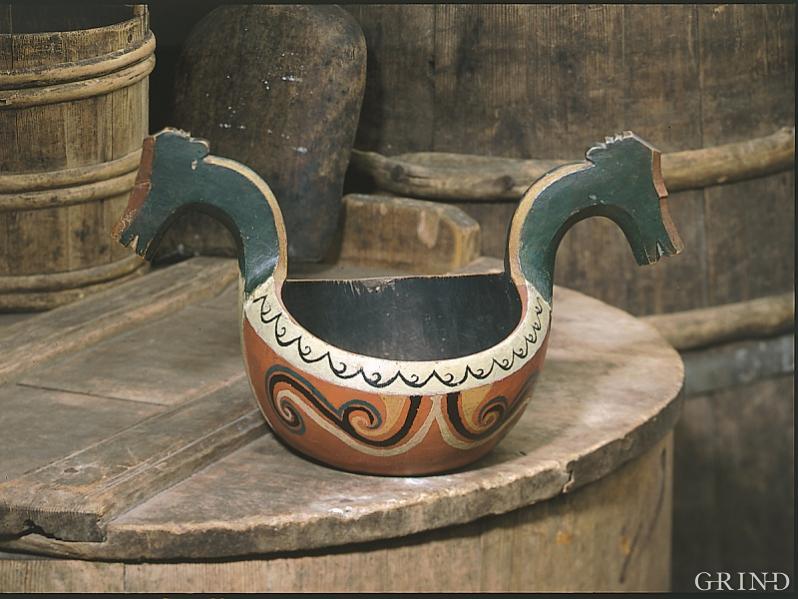

In 1782 two brothers came across the mountains from Hallingdal and down to Eidfjord. They came from Hammarsbøen in Hol and travelled over to the west of Norway to try their luck. At Bu they visited the house of Amund Johannesson and painted some of the things he had there, including a beer tankard which was inscribed with the hospitable sentiment: “Drink and be happy/ my dear neighbour/Here there is enough for us both, Amund Johane sen, Bu in the Year 1782”.

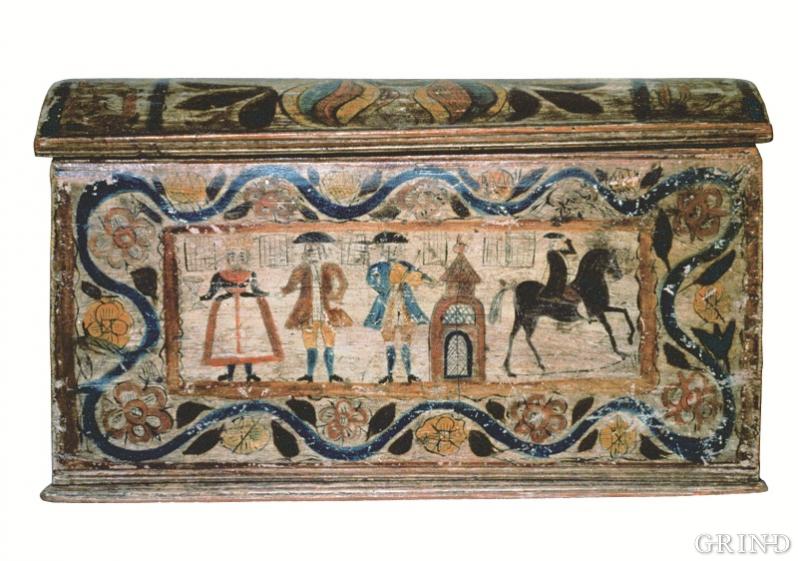

The two brothers Svein (1766-1809) and Vebjørn Hammersbøen (1761-1808) travelled on out to the fjord, and next year they came again, and likewise the year after. And so we can follow their journey from Eidfjord and out to Kvam and Strandebarm. In Øystese they painted a chest for “Brita Jans Daughter Østense in the year 1784”, the daughter of “the potato law officer”. He was the law officer for Rosendal estate in Kvam and was engaged in sloop transport, as well as running the farm.

But the next year in 1785 the Hammarsbøen brothers took a different route. Then they went through Sørfjorden and Oddadalen, and probably also took a trip down to the rural districts in Sunnhordland. In 1786 we see that they travel through Hålandsdalen and other rural districts in Midthordland. Here local tradition says that the local painters in Samnanger learned the painting trade from the travelling painters from Hallingdal. This was probably these two brothers from Hol.

In this way we can reconstruct the painting journeys of Svein and Vebjørn. As far as we can see they were annual guests in the rural districts in Hardanger and Sunnhordland in the 1780s.

A new church was built in Åkra in 1735. In 1787 the Hammarsbøen brothers were given the task of doing the painting of the interior: “The church is said to have been painted in the year 1787 by the two painters, who were at that time, famous, Svenn Olsen and Vebjørn Olsen from Hammarsbøen in Hallingdal” wrote the law officer Christopher Løwig in 1870 after the old church was rebuilt. It is clear that those two from Hallingdal had achieved a good reputation and were not afraid to take on such a large task as decorating a church in a little rural district in the fjords in western Norway, with great vine branches and Biblical figures, in the decorative tradition of the guild painters of the 17th century.

Vebjørn continued with the trade. He went to Nordfjord where he leased a site on the Tjugen farm at Loen in 1799. Svein got married in Rogaland County. There he settled down as a merchant and a ship-owner. And so we get a little close-up picture of two young men from Hallingdal who wander far and wide in their youthful days, before each of them settled down in his own spot with his own livelihood - tale which shows us how the handicraft travels were part of a greater economic system between the rural districts.

Crafts and handicrafts in the rural districts

It is probably more than a random occurrence that the Hammersbøen brothers turn up in Eidfjord in 1782. In the same year the powers-that-be had partly repealed the regulations of 1746 requiring that crofters and others who practised a trade in the rural districts pay tax. The exemption of 1782 was, in reality, a modification of the old guild privileges which monopolised the finer trades for the professional tradesmen in the cities. Even although it had probably been difficult to operate effective controls over cheats out in the rural districts, we have to assume that rural painters could now, to a greater extent than before, move around to other districts and offer their services, without being branded as “cheats and swindlers”.

The handicrafts influenced by home crafts in rural society has been presented in classical form in Eilert Sundt’s book of 1878 “On Home Crafts in Norway”; in which he terms “general skills in the rural districts”. Rural handicrafts are distinguished from home crafts by the degree of specialisation and from professional craftsmanship, by being typical seasonal work, and a secondary trade. A large part of popular art belongs in this category. In the census of 1801 the ratio of craftsmen to farmers in Southern Bergenhus County was 1 to 200. This shows us primarily that many people had a craft as a subsidiary job which does not show up in the statistics. In 1865 the situation was different. Then the craftsmen have grown into a large group of workers, and rural society is poised at the transition to factory production and semi-manufacture.

The craft district of Voss was known for its many good smiths; joiners and carpenters. In the rural districts around Voss wooden carving was predominant; it is the carved pattern’s geometrical motifs which decorate boxes and chests in Voss as in Setesdal - the two districts in Norway most strongly influenced by the Middle Ages traditions.

But there were many good farms in the Voss area, and when we reach the 19th century there is little wonder that the travelling painters make their way through Voss. There was money to earn here.

Renaissance forms and baroque colours

The Hammarsbøen brothers were influenced by the painting milieu around Kittil Rygg in Hol and the guild tradition from the 17th century. The classical Renaissance vine branches and the decorative motif repertoire are a special feature of the flowering Baroque around the middle of the 17th century, acanthus branches, clusters of grapes, roses, rosettes, figures and pictorial motifs in a strongly coloured style: ochre, cinnabar, Berlin blue and English red, with black contours against a light grey background. Both the colours and the decorative motifs – urns, cartouches, roses and rosettes - have lived for a long time in popular art. We get an impression of this decorative guild art in Målabuo at Gjerde in Mauranger, in the churches at Kinsarvik and Eidfjord and in the bedloft at Helleland in Lofthus.

Another of the early artists from Hallingdal, LARS ASLAGSEN TRAGETON (1770-1839) settled at Nedstrand in Ryfylke. He must have been the master for GUNDER GUNDERSEN HANDELAND (1794-1871) from Halsenøy who was a productive painter in the rural districts of Sunnhordland for many years. Handeland also like pictorial motifs; we know two unique versions of his portrayal of the three pillars of society - with the seafarer and the fisherman in addition to the farmer, the priest and the officer. It is a picture with a polemical sting: “producers” against “consumers”- public servants in local society.

IMAGES AND SYMBOLS

One of the most prized Renaissance motifs is the flower vase with roses, lilies and tulips. The roses are the lilies are the Middle Ages’ central motifs in the symbolic traditions of the Christian church, linked to the tales relating to the Virgin Mary.

The inscription which follows tells us that the flower vases are bearers of a symbolic value which lies deeper than pure aesthetics:

“Let thy heart be like a pot, full of the spiritual life’s blossoms”, a so-called homiletic motif (homiletic being in the style of a sermon).

The flower vase can be portrayed together with a motif like Samson and the lion - a pre-figuration motif – or the deer, an ancient baptism symbol: “As the deer thirsts after running water, so thirsts my soul after the Holy Spirit” (from the “Psalms” ). That such tales can have been alive in the popular mind during the first century after the reformation is probable; but when the symbolic content was lost in the tradition is, however, unclear.

THE TELEMARK FOLK IN THE FJORD DISTRICTS

But let us return once more to Hardanger and to the fjord districts. In the 1790s we see that there were several peripatetic painters on the go, although we cannot be sure who they all were.

In the first decade of the 19th century several painters from Telemark must have travelled through Hardanger and the Sunnhordland districts, but it was first around 1820 that the big expansion came, “the exodus from Telemark”. From then onwards for 40-50 years the folk from Telemark were annual visitors and this traffic did not culminate before emigration to America took off.

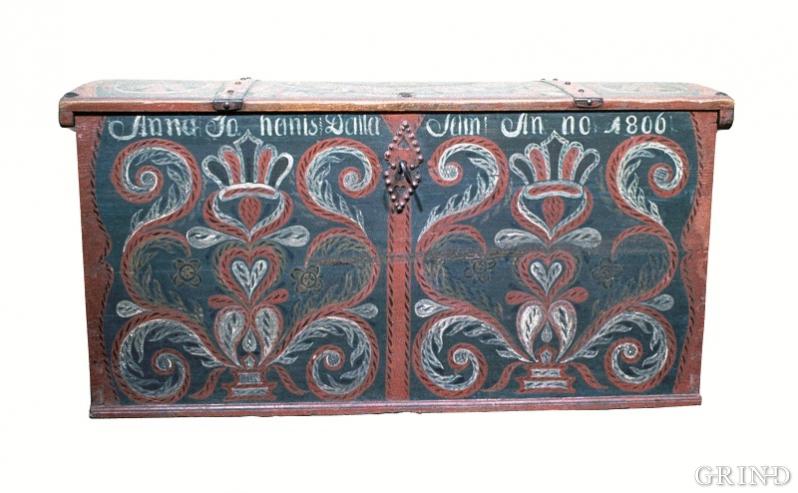

During this period it was primarily the Telemark painters who put their stamp on the craftsmen’s travels to districts in western Norway. There were many young men who travelled out from small hamlets in Telemark to try their luck. Very many of them chose painting and it is remarkable that so many had such a talent for this craft. Between 40 and 50 painters must have visited the fjord districts; that is to say almost 40% of the painters in Telemark. And not a few came back to painting trips on a regular basis over a long period. According to tradition the LURAAS brothers from Tinn often travelled together. They were also fiddlers, and mastered both the fiddle and the clarinet. We can see that THOMAS (1799-1866) who was the better known of the two, has travelled through Hardanger and Midthordland every three or four years from the 1820s up until 1860. Bjørn Bjaalid was also a frequent guest; one of the most elegant painters and an exuberant teller of folk tales.

SCARF BOXES AND CHESTS FOR SALE

The scarf box in Hardanger was a specialised form of handicraft production, distributed over the whole area where the old folded scarf was used. Both the technique and the painting show that they were produced in large numbers and sold as a finished handicraft product.

Folk from Telemark made a breakthrough and created a fashion in the rural districts of Hardanger. The new generation of local painters who started painting around 1830 can be characterised as a Telemark School. With TROND LARSON HUS (1806-1871) in Kinsarvik we come over into a new and interesting phase. “Trond i Vikje” set up a more series type of production of chests. He wanted, to a greater extent, to depend upon painting as a livelihood, and, in addition to normal jobs like painting chests and cupboards on order from people in the district, he began to paint chests for sale, so-called “sale chests” . Most usually these chests were only inscribed with the year. Many of them also had room for initials which could be put on when they were purchased.

It is hardly to be wondered that the people of Hardanger exploited this handicraft production commercially. In these districts there were well incorporated traditions of trading and sailing traffic. Right north to Nordfjord folk from Hardanger went and sold bedspreads in the18th century, and we can see the same in the records of inheritance from Øygarden and Sotra in the 1770s. The sales chests in the 19th century were shipped on sloops to Bergen and southwards to Haugesund and Stavanger. The sloops sailed fully loaded with fruit and chests which were either sold directly from the boats on Strandkaien or through farm traders. Up to one thousand chests were exported ever year from Sørfjorden.

“STRILE” CHESTS FROM OSTERØY

The export of Sole chests was at its height from Hardanger around the middle of the 19th century before the “Hardanger chests” began to feel the competition from other districts. After the middle of the 19th century a cottage industry grew up completely in parallel with the sole chest production in Sørfjorden. Especially in Lonevåg and in Hosanger there was a production centre for the chests from Osterøy, and there were not just a few folk who were employed on chest production, carpentry, forging and painting. The chests got a simple, patterned design as in Ullensvang. But the colours and the motifs on the other hand were quite different. While the sole chests have simple Telemark roses with a red background, the ostra chests have small roses, set in the middle, often with shaded dark red, marine blue or Kassel brown backgrounds.

In Hosanger it was around 1865 that they started to work on chests for sale to Bergen. JON LARSSEN BØRNESET MJØS (1825-1913) was actually a blacksmith, but he built a house in Mjøsvågen and started up with chest production.

Jon Mjøs did well with his chest production and needed more room. He built a new house further up Mjøsvågen, with storage for materials downstairs, and two rooms upstairs; one for joinery and one for fittings and painting. As time went by, five chest workshops developed in Hosanger, but it was always Jon Mjøs, and later his son-in-law Las A.Mjøs who had the biggest workshop.

THE OS PAINTERS AND THE HOME CRAFTS MOVEMENT

In the farmers’ hostels (bondestovane) on Strandsiden they took in many of the wayfarers from other rural districts when they were visiting the city, the pedlars from Voss, folk from the East and farmers from the fjords, grocers, rose-painters and musicians. There must have been many impulses which crossed one another in that popular cultural environment in the city, and here Ole Bull surely heard the first notes of the Hardanger fiddle. Here you could buy yourself a Hardanger chest, a chest from Osterøy, small boxes from Viksdal and many other items from the rural districts around Bergen, and - from the end of the 19th century - chests, chairs and boxes from Os - painted white with highly coloured roses.

One of those who had the best reputation in western Norway as a rose painter was ANNANIAS TVEIT from Os (1847-1924). But his slightly older companion from the same village, OLA MIDTBØ (1831-1925) was an especially capable painter. These painters from Os illustrate the transition from the mobile district crafts production to the stationary workshop production. It is interesting that this took place so late in the 19th century that these painters were also the first suppliers to the newly established craft sales outlets for the Home Crafts Association of western Norway in Bergen in 1896, in the years before photography made an appearance as a pictorial medium in the rural districts.

Right up to the beginning of the 19th century Annanias travelled on his painting trips outside the harvest season. At that time he came into contact with a merchant in Bergen, Richard Arnesen, and he spent some time at home with Arnesen and painted things which were sold in the shop. But after some years Annanias Tveit set up a rose painting workshop on his home farm. The craftsman had become a producer of home crafts. And that is where the circle closes.

- Brekke, N. G. (1968) Rosemåling i bygdene kring Hardangerfjorden. Magisteravhandling, Universitetet i Bergen.

- Brekke, N. G. (1980) Rosemåling i Midthordland. I: Engevik, A. K. red. Bygdesoga for Os: kulturhistorisk band. Os, Os sogenemnd, s. 221-334.

- Brekke, N. G. (1981) Rosemåling i Sunnhordland. I: Sunnhordland Årbok. Stord, Sunnhordland museum, s. 8-51.

- Brekke, N. G. (1983) Bygdehandverk, husflid og heimeindustri. Dugnad, 4, s. 3-24.

- Brekke, N. G. (1988) Austmenn i Fjordbygdene: handverkarvandringar og kulturkontakt mellom Telemark og Hardanger på 1700- og 1800-talet. I: Årbok for Telemark. Seljord, Stiftinga Årbok for Telemark, s. 132-149.

- Trætteberg, G. (1952) Omfarshandel: skreppekarer, driftekarer og jekteskippere i Hordaland. Norveg, 2. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget.